Python

The Interpreter

The Python bytecode interpreter e.g. what is installed on /usr/local/bin/Python3.13 can read and execute commands interactively or read and execute Python scripts.

How does Python code run?

First the python code is compiled into bytecode and stored as .pyc files in __pycache__. An example might be:

print("Hello")

Compiles to

LOAD_NAME 0 (print)

LOAD_CONST 0 ('hello')

CALL_FUNCTION 1

POP_TOP

LOAD_CONST 1 (None)

RETURN_VALUE

The Python interpreter program consists of a loop (bytecode evaluation loop) that iterates over bytecode instructions, fetching one bytecode instruction at a time. It decodes the bytecode instruction, and executes the corresponding C function. This is also referred to as the CEval loop.

The flow of execution for CPython is:

source code -> bytecode -> interpreter loop execution

Each bytecode instruction maps to a function in ceval.c.

A very useful source from Python docs: the bytecode interpreter.

Iterables, Iterators, Generators

An iterable is any object that can return an iterator.

An iterator is a helper object that produces the next value given an internal state. An iterator can be thought of as a lazy value factory that provides a value only when requested. It is possible for iterators to produce infinite sequences and never terminate.

An iterable implements __iter__() which returns an iterator object, and an iterator implements __next__() and returns the next value, raising StopIteration exception when no more elements are available.

You can manually get the iterator from an iterable using iter() and the next value from an iterator using next().

For instance, an iterator might be implemented using two distinct patterns. With pattern A, you have both the iterable and the iterator as one class - the iterable is its own iterator. In this case it can only be consumed once since the iterable maintains iterator state itself. In pattern B, you have a separate iterable and iterator, with __iter__ returning a fresh iterator each time (this one is more Pythonic and canonical).

# Pattern A: Iterable is the iterator

class ChunkedRange:

def __init__(self, rangeStart, rangeStop, chunkSize):

self.rangeStart = rangeStart

self.rangeStop = rangeStop

self.chunkSize = chunkSize

self.cur_val = rangeStart

def __iter__(self):

return self

def __next__(self):

if self.cur_val >= self.rangeStop:

raise StopIteration

lst = []

stop_val = self.cur_val + self.chunkSize

stop_val = min(stop_val, self.rangeStop)

while self.cur_val < stop_val:

lst.append(self.cur_val)

self.cur_val += 1

return lst

# Pattern B: Iterable and iterator are separate

class ChunkedRangeIterable:

def __init__(self, rangeStart, rangeStop, chunkSize):

self.rangeStart = rangeStart

self.rangeStop = rangeStop

self.chunkSize = chunkSize

def __iter__(self):

return ChunkedRangeIterator(self.rangeStart, self.rangeStop, self.chunkSize)

class ChunkedRangeIterator:

def __init__(self, rangeStart, rangeStop, chunkSize):

self.rangeStart = rangeStart

self.rangeStop = rangeStop

self.chunkSize = chunkSize

self.cur_val = rangeStart

# An iterator is also an iterable!

def __iter__(self):

return self

def __next__(self):

if self.cur_val >= self.rangeStop:

raise StopIteration

lst = []

stop_val = min(self.cur_val + self.chunkSize, self.rangeStop)

while self.cur_val < stop_val:

lst.append(self.cur_val)

self.cur_val += 1

return lst

Canonically, iterator classes even if it is defined separately from the iterable should still implement __iter__() and return self. This is because in Python an iterator is an iterable over itself and calling iter() on an iterator should returns itself (even if it is partially consumed).

Iterables can return themselves as the iterator, by implementing both the __iter__() and the __next__() method, so __iter__() returns self.

Calling iter() on an iterator should also return itself.

So what happens during a for loop? The for loop calls iter() on the target object to get its iterator and then exhausts it. The syntax for x in iterable calls iter(iterable) to get an iterator, and then exhausts the iterator until StopIteration is thrown. Take the code for x in range(0, 10). Here, the object range(0, 10) is an iterable which can provide an iterator when iter(range(0, 10)) is called.

A generator is a subset of iterators. They exist to provide a shortcut to building iterators, by allowing you to write an iterator without needing an explicit __iter__() and __next__() methods. It can take the form of a generator function (with yield) or a generator expression.

For instance, you can write a generator function like so:

def firstn(n):

num = 0

while num < n:

yield num

num += 1

sum_of_first_n = sum(firstn(100000))

When a generator function is called, it returns an iterator known as a generator.

A yield expression in any function body turns it into a generator function. Think of the yield as a return that does not end the function, it simply suspends the state. The next time the generator function executes, it proceeds from where it was last paused. When the generator reaches the end of the function or a return statement, it raises StopIteration.

Hence, this will return the sequence 1, 2, 3:

def foo():

yield 1

yield 2

yield 3

A cool quirk of generator functions is that they are not just for one way communication from the generator to the caller with next(). They also enable the caller to communicate with the generator to modify its execution via a send(). A yield expression actually will take on the sent value after resuming. Thus generators are coroutines.

What is a coroutine?

A coroutine is a program that allows execution to be paused and then resumed later.

Python has bidirectional coroutines. They allow bidirectional communication at suspension points so that it is possible to resume execution with new information.

def echo(value=None):

while True:

try:

# here the expression (yield value) can change based on send

value = (yield value)

except Exception as e:

value = e

You can also create generator expressions which are additional shortcuts to build generators out of expressions similar to list comprehensions:

# list comprehension

doubles = [2 * n for n in range(1000)]

# list from generator comprehension

doubles = list(2 * n for n in range(1000))

A generator is a special type of iterator, but iterators are not necessarily generators. Generators provide a quick and easy way to create iterators and build lazy generation of values with the main advantage being low memory usage.

Generators are powerful tools to make your code more memory and CPU efficient. Whenever you see:

def func():

result = []

for x in ...:

result.append(x)

return result

Try to replace it with:

def iterator_func():

for x in ...:

yield x

# when you need the full list just do

result = list(iterator_func())

For more info, consult this helpful resource with diagrams here.

zip()

A very useful utility function in Python is zip() which takes any number of iterables, and combines the iterables into one iterator of tuples. Once the shortest iterable is exhausted the iterator terminates (hence the iterables do not have to be the same length everywhere).

# Example from my flood mapping project

channels = [True, False, True, True, True]

channel_names = ["red", "green", "blue", "nir", "swir"]

for item in zip(channels, channel_names):

print(item)

# (True, "red")

# (False, "green")

# (True, "blue")

# ...

To unzip a list of tuples, the inverse of the zip() operation is zip(*iterable), which returns the original groups as tuples:

zipped_list = [(1, "one"), (2, "two"), (3, "three")]

nums, words = zip(*zipped_list)

print(nums)

# (1, 2, 3)

print(words)

# ("one", "two", "three")

A more pythonic and less error free (since zip(*iterable) cannot handle an empty list) just use list comprehension:

lst1 = [x[0] for x in zipped_list]

lst2 = [x[1] for x in zipped_list]

map()

The function takes the form map(function, iterable, strict=True) and returns an iterator that applies the function to every element of the input iterable.

Multiple iterables can also be provided, in which case the function must take as many arguments and applies to the iterables in parallel. If strict=True then if one of the multiple iterables gets exhausted before others, a ValueError gets raised.

Class Attributes

As opposed to instance attributes, class attributes are shared across all instances of a class:

class Dog:

species = "Canis familiaris" # class attribute

def __init__(self, name):

self.name = name # instance attribute

Class attributes are also mutable, but this is not safe. By convention, class attributes are used for immutable things, while instance attributes serve to store mutable things.

Decorators

What are python decorators for?

The motivation of decorators in Python is to apply some transformation to a function or method. This allows for simple modification or extension of the function behavior (think of it as taking a function, wrapping it in additional functionality, and replacing the original function). For instance, the snippet:

@dec1

@dec2

def func(arg1, arg2, ...):

pass

is no different in its intent than the snippet:

def func(arg1, arg2, ...):

pass

func = dec2(dec1(func))

Decorators can be stacked, which can be thought of as composing them together! For instance,

@decomaker(argA, argB, ...)

def func(arg1, arg2, ...):

pass

is equivalent to:

func = decomaker(argA, argB, ...)(func)

Here are the most common decorators you should know:

@property- turns function into property or attribute style getter e.g.Circle.areato get the value@classmethod- useclsinstead ofselfto call function, so receives the class itself as the first argument. Usually this is used for alternative constructor functions that provide other ways to instantiate an object - you pass inclsthen it returnscls(name, int(age))for example.@staticmethod- defines method withoutselfhandle that lives in the class namespace so it doesn't depend on instance or class e.g.MathUtils.add(3, 4)@abstractmethod- makes a method that must be implemented

Abstract Base Classes (ABC)

An Abstract Base Class has the property that it cannot be instantiated directly, only inherited like an interface. A class that inherits from an ABC must implement all of its abstract methods.

from abc import ABC, abstractmethod

class Animal(ABC):

# every subclass of Animal must implement speak()

@abstractmethod

def speak(self):

pass

Abstract classes can still have regular class attributes and methods that get inherited by children:

class Animal(ABC):

species = "Unknown" # class attribute

def __init__(self, name):

self.name = name # instance attribute

Data Classes

The python dataclasses decorator dataclass allows you to create structs (will automatically generate boilerplate __init__ constructors). That way you save yourself having to create an __init__ with all the struct arguments and then storing them in self.arg = arg.

The way it works is that the decorator will look for fields in the class which are class variables with type annotations, and generates the methods with the fields in the order they were defined in the class.

from dataclasses import dataclass

@dataclass

class Box:

name: str

unit_price: float

quantity: int

def total_value(self) -> float:

return self.unit_price * self.quantity

# Automatically generated so we don't need this:

# def __init__(self, name: str, unit_price: float, quantity: int):

# self.name = name

# self.unit_price = unit_price

# self.quantity = quantity

field

You will find it useful to also import field method from dataclasses module.

A field is by default implicitly run for each annotated class variable defined in the dataclass. A class variable name: str is implicitly treated as name: str = field() with no arguments, so it's default value is set to None. When you initialize a class variable y: int = 5 in the class definition, the default is passed into the field method like y: int = field(default=5).

A point of confusion to avoid is whether the varariable is shared among all instances or particular to an instance variable. See the following nuance:

@dataclass

class Person:

names: List[str] = []

p1 = Person()

p2 = Person()

p1.names.append("Dave")

print(p2.names) # ['Dave'] - it's shared!

But if we do this it is unique to each instance:

@dataclass

class Person:

names: List[str] = field(default_factory=list) # not [] as it expects a callable

p1 = Person()

p2 = Person()

p1.names.append("Dave")

print(p2.names) # [] Not shared!

What happens is that in the first example the list gets created at class definition time, resulting in each of the dataclass instances inheriting the reference to the same list object. In the second example the list gets created during instance construction, so the list for each instance is unique.

Python class attributes:

In learning about this, I think I had a misconception about regular Python class attributes, in that once they are initialized, they will always be shared by instances. If the instances tried to override them, the replaced value is still shared across variables.

The reality is that the initialized value at class definition time is shared among instances, but instances are free to override the attribute namespace and set a value for themselves (that does not get propagated to the other instances)!

At class definition time, any attributes assigned at the top without __init__ become class attributes. When instances lookup attributes, they first check their own __dict__ and if not found will default to the attribute until it gets shadowed.

Thus @dataclass does not break the rules of regular Python when it comes to the behavior of class variables and instance variables. It just generates boiler plate code __init__, __repr__, __eq__ etc. so you do not have to.

Now if you want to specify kwargs for the field beyond the default, you can pass that in explicity with options such as default, default_factory, init, repr:

from dataclasses import dataclass, field

@dataclass

class Box:

name: str

unit_price: float

quantity: int = field(repr=False) # field not included in string representation

width: int = field(repr=False, default=5)

The dataclasses field is not to be confused with the Pydantic Field. The concept is the same and Pydantic fields are also similarly defined by type annotations with customization with Field. The point of field across both cases is to represent a well designed class attribute for data storage and manipulation.

Python Packages

One thing I have learned when working with Python projects is that is important before starting to think about the audience and the environment you want to run the program in. If you want to deploy and share your code for other developers or users, having this figured out before hand saves a lot of headache later on. Otherwise you will find yourself in a mess trying to restructure your project into a proper package way down the line.

Packages helps consolidate a growing collection of modules or python scripts, so you have dotted module names, e.g. A.B for submodule B in package A. The __init__.py scripts make directories containing the file as packages.

__init__.py

In the simplest form, __init__.py can be empty - it marks directory it is in as a python package. You can also add initialization code inside __init__.py to import certain functions/classes or run setup code when the package is imported. A key functionality to allow you to setup a package's namespace upon import.

The __all__ inside a package's __init__.py is interpreted as a list of module names to be imported with the statement from package import *. The purpose is simply to allow the import * syntax, otherwise it is unnecessary.

# from sound.effects import * -> imports three submodules

__all__ = ["echo", "surround", "reverse"]

What about the other stuff typically in a __init__.py file? When you add these statements into the __init__.py, the submodules are explicitly loaded when the package is imported:

"""

AI Flood Detection Package

This package contains modules for flood detection using satellite imagery,

including data preprocessing, model architectures, training, and inference.

"""

__version__ = "1.0.0"

__author__ = "Hydrosm DMA Team"

# Make key components easily importable

from . import models

from . import utils

from . import training

from . import preprocess

from . import sampling

from . import inference

from . import benchmarking

from . import tuning

With empty __init__.py, python behavior is lazy and will only import the module from the package and run it when it is explicitly imported. If you add from .training import train_s2, then train_s2 is a floodmaps attribute i.e. accessible with floodmaps.train_s2. Consequently it makes things easier to import from a top level like from floodmaps import train_s2. Similarly, if you do from . import models inside __init__.py, now it is loaded in under floodmaps. Instead of import floodmaps.models you can simply do import floodmaps and automatically have floodmaps.models bound in its namespace. You could also do from floodmaps import models - without it, this will throw an import error!

It can be confusing at first but it's all about bringing things into scope. A simple import X binds the module to the name X. A from X import Y looks inside the namespace of X and adds Y to the current scope. If you want something directly inside namespace without needing to do floodmaps.training you will have to explicitly request it. Hence the __init__.py autoimporting can be a useful feature.

If there is a submodule multiple directories deep, to make it more accessible at top level,you can add from .models.training.utils.package import function in __init__.py. Then do from floodmaps import function in any script you want. Reduces the problem of a long from floodmaps.models.training.utils.package import function import line.

# Expose commonly used utilities

from .utils.config import Config

from .utils.utils import DATA_DIR, RESULTS_DIR, MODELS_DIR

Adding this allows you to do from floodmaps import Config, DATA_DIR, RESULTS_DIR, MODELS_DIR instead of from floodmaps.utils.config import Config etc.

In modern python with implicit namespace packages, __init__.py is often not needed as folders will automatically be treated as packages if you try to import from it. However, it's still better to have it in order to be explicit about your code as a package. You'll probably want to customize the symbols in the namespace using __init__.py anyways.

One really useful thing for example when starting out is to pip install the repo as editable pip install -e. This allows you to sidestep annoying relative imports in a multiscript project.

PYTHONPATH

The PYTHONPATH is an environment variable commonly set to tell the python interpreter where to look for modules and packages before standard locations, extending the import search path. From the python docs it "augments the default search path for module files". However, if you have your python project configured as a package, you can install it with pip install -e . which adds your package path so it can be found.

export PYTHONPATH=/home/user/myproject

Closures

A closure happens with a function defined inside another function. The inner function grabs the outer variables defined in its enclosing lexical scope and remembers them even when the function is executed outside of that scope - the combination of a function and its enclosing scope is a closure. This is common in functional programming languages and is the case in Javascript as well.

For instance, if you returned this inner function, it still remembers the variable name in its surrounding scope.

def outer_func():

name = "Pythonista"

def inner_func():

print(f"Hello {name}")

return inner_func

greeter = outer_func()

greeter()

# Hello, Pythonista

Parallelization

There are different main ways to parallelize code in Python: multiprocessing and concurrent.futures packages.

multiprocessingis designed for parallelism for processes to bypass the GIL.concurrent.futuresprovides simpler API for both thread and process parallelsim. The packageconcurrent.futuresis designed to be a more consistent API around threading and processes. In most cases,concurrent.futurescan be used instead ofmultiprocessing.

Within concurrent.futures you will commonly use ThreadPoolExecutor and ProcessPoolExecutor.

An important distinction when designing parallelization in Python is thinking about whether the task is I/O bound or CPU bound. If it is I/O bound the recommendation is to use ThreadPoolExecutor and threads that share memory as you can bypass the GIL lock.

Global Interpreter Lock (GIL)

The Global Interpreter Lock in Python is a mutex (lock) that allows only one thread to hold control of the Python interpreter and execute Python bytecode in a single process at one time. Hence even if your process spawns multiple threads, only one thread can execute at one time, which bottlenecks CPU bound multithreaded code.

Why does this exist?

The main reason for the GIL is to ensure memory safety. CPython uses reference counting to manage memory, where a reference count variable tracks the number of references to an object. When the count goes to zero, the memory is released.

Locks are needed to protect the reference count variable from race conditions which can leak memory or cause in-use memory to be released early. A solution is to have a lock for atomic updates to each reference counter, but adding a lock for each object can lead to too many acquisitions and releases of locks or deadlock situations. The solution was therefore a singular lock over the interpreter called the GIL.

The Global Interpreter Lock is necessary because CPython memory management (with respect to reference count variables) is not thread-safe.

Since we cannot truly have multithreading in Python, the common approach is to use multiprocessing, where you use multiple processes instead of threads. With multiprocessing, each Python process gets its own Python interpreter, memory space, and GIL. It enables parallelism while adding slightly more overhead than multithreaded approach.

A notable exception is that the GIL lock is released during I/O operations, so I/O bound threads can benefit from multithreading in Python. Thus, multithreading is only bottlenecked by the GIL when the program is spending most of its time interpreting CPython bytecode.

It is also the case that NumPy releases the GIL for low level operations, hence a lot of numpy operations can run in parallel with multithreading.

Context and Start Methods

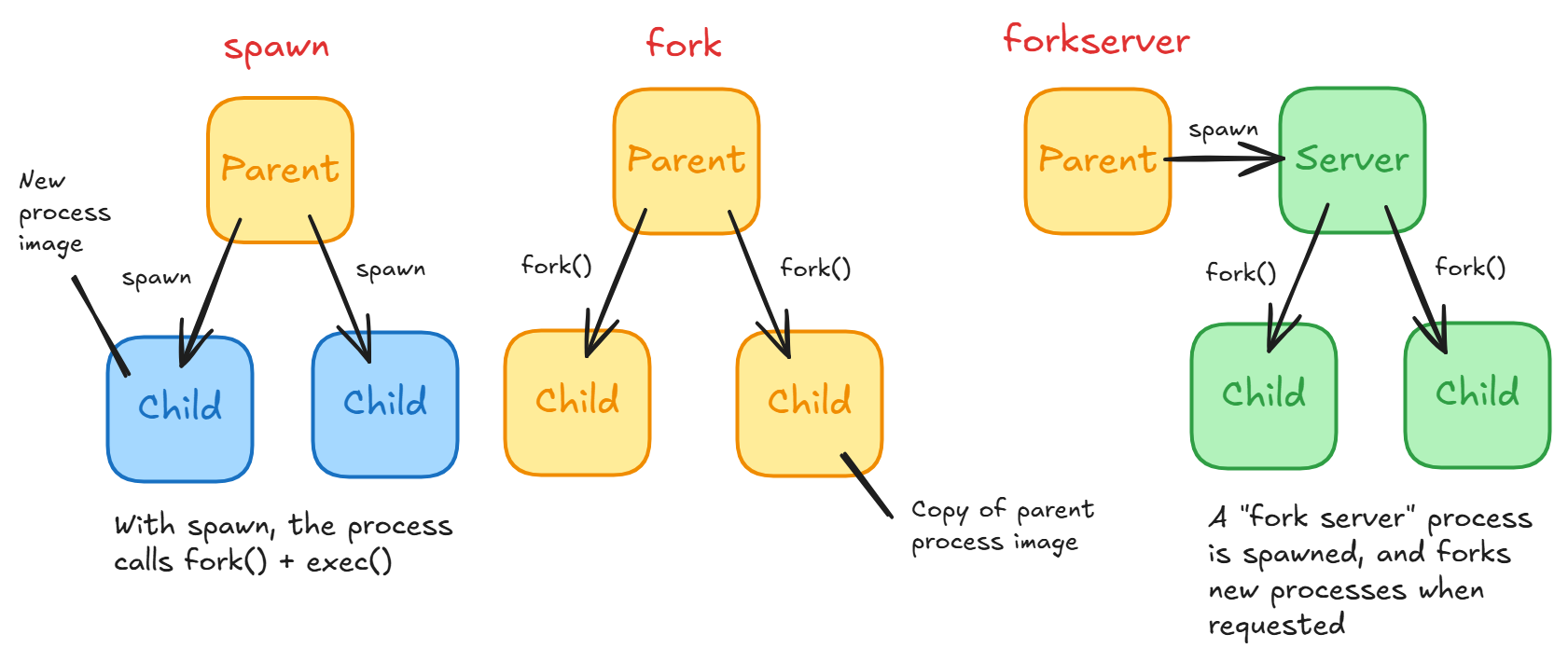

Important to both multiprocessing and concurrent.futures (which uses multiprocessing throughout) with respect to running multiple processes is the different process start methods. Understanding this will be useful to properly employing ProcessPoolExecutor. There are three ways:

spawn- The parent process starts a fresh interpreter process so the only resources inherited are what's needed for the process object'srun()method.fork- The parent process usesos.fork()to fork the Python interpreter. This means that all memory from the parent process is inherited including the Python interpreter, loaded modules, and objects (see below for details). For multiple processes, they can share the same pages in memory (with Copy-On-Write) as they are marked read-only. It is dangerous to fork for multithreaded processes.forkserver- A hybrid betweenforkandspawnthat reduces overhead of spawning workers. The concept is simple: have a separate Python server with simpler statefork()itself when a new process is needed. Each time you start a child, it asks the "fork server" process to fork a child and run its target callable.

What happens during a fork?

With an os.fork() call, you are calling the underlying C fork implementation here. fork() creates a new process by duplicating the calling process. The child process is the exact copy of the parent process except the child process has its unique PID. The child and parent processes have their own virtual memory address space. However, at the time of call, both memory spaces map to the same physical content or pages.

Things to remember:

- The entire virtual address space of the parent is replicated in the child via a copied page table.

- The child inherits a duplicate of the parent's file descriptor table.

fork()is implemented with copy-on-write (COW) pages. This means only the page table and PTEs of the parent is copied and not the actual underlying memory pages. Furthermore, the shared memory pages in both parent and child page tables are marked read-only.forkis problematic when called in a multithreaded process, because the child process will only be a single thread, the thread that calledfork(). But all of the memory including memory of the other threads will still get duplicated including the state of their stack, locks, data structures etc. Say you have Thread A and Thread B. Thread A callsfork()while Thread B is holding a mutex. Then after the fork the child process still has access to this mutex which got duplicated, but it appears held while the thread holding it has vanished. If the child process attempts to use the lock you get a deadlock.

Copy-on-write:

- Allows for efficient forking because copying the entire memory of parent process is too costly an operation.

- Why are pages marked read-only in both parent and child? Should it not just be the child? Since both parent and child share the mappings to the same physical page, you want to make sure that for isolation, neither of them must see the other's modifications. Hence, when the parent or the child modifies a page, a new page must be allocated.

What happens during spawn?

To create a fresh child process without the parent process' memory, spawn first forks the current process, followed immediately by exec to replace itself with a new Python instance.

exec() replaces the current process image (program code, data, heap, stack, PCB) with an entirely new process image, with the argument as the file to be executed.

multiprocessing.Queue

An extremely important component of the multiprocessing Python package is the Queue class. The queue structure is the fundamental way to share data between processes. The queue allows for items to be added with put() and retrieved with get() with items retrieved in FIFO order.

Everything that goes through the queue must be picklable. As per the docs:

Note that the restrictions on functions and arguments needing to picklable as per multiprocessing.Process apply when using submit() and map() on a ProcessPoolExecutor.

Arguments passed into process workers while using multiprocessing or concurrent.futures are serialized and hence must be picklable.

matplotlib.pyplot

Transformations

There are multiple coordinate systems in matplotlib:

- data coordinate system (

ax.transData) - axes coordinate system (

ax.transAxes) - subfigure coordinate system (

subfigure.transSubfigure) - figure coordinate system (

fig.transFigure) - display coordinate system (

NoneorIdentityTransform())

These Transform objects are naive to source and destination coordinate systems - they take inputs in their coordinate system and transform the input to the display coordinate system. Thus display coordinate system is None as the input is already in display coordinates.

Transformations can invert themselves with Transform.inverted in order to generate a transform from the output coord system (display) to the input coord system. For example, ax.transData.inverted() transforms display to data coordinates.

Transforms are important because they specify what coordinate system you are using, and map it to the display.

Numpy

Basic Indexing

- Single element indexing -

x[1, 3] - Slicing and striding -

x[1:7:3](start:stop:step)- Reverse -

x[::-1]

- Reverse -

- Dimensional indexing

- Ellipses -

x[..., 0](...expands to number of:to index all dims) - New axis -

x[:, np.newaxis, :, :]orx[:, None, :, :](np.newaxisis just an alias forNone)

- Ellipses -

Advanced Indexing

Advanced indexing in Numpy involves indexing with a nd.array or a non-tuple sequence.

For instance, you can do:

x = array([10, 9, 8, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2])

x[np.array([3, 3, 1, 8])]

# array([7, 7, 9, 2])

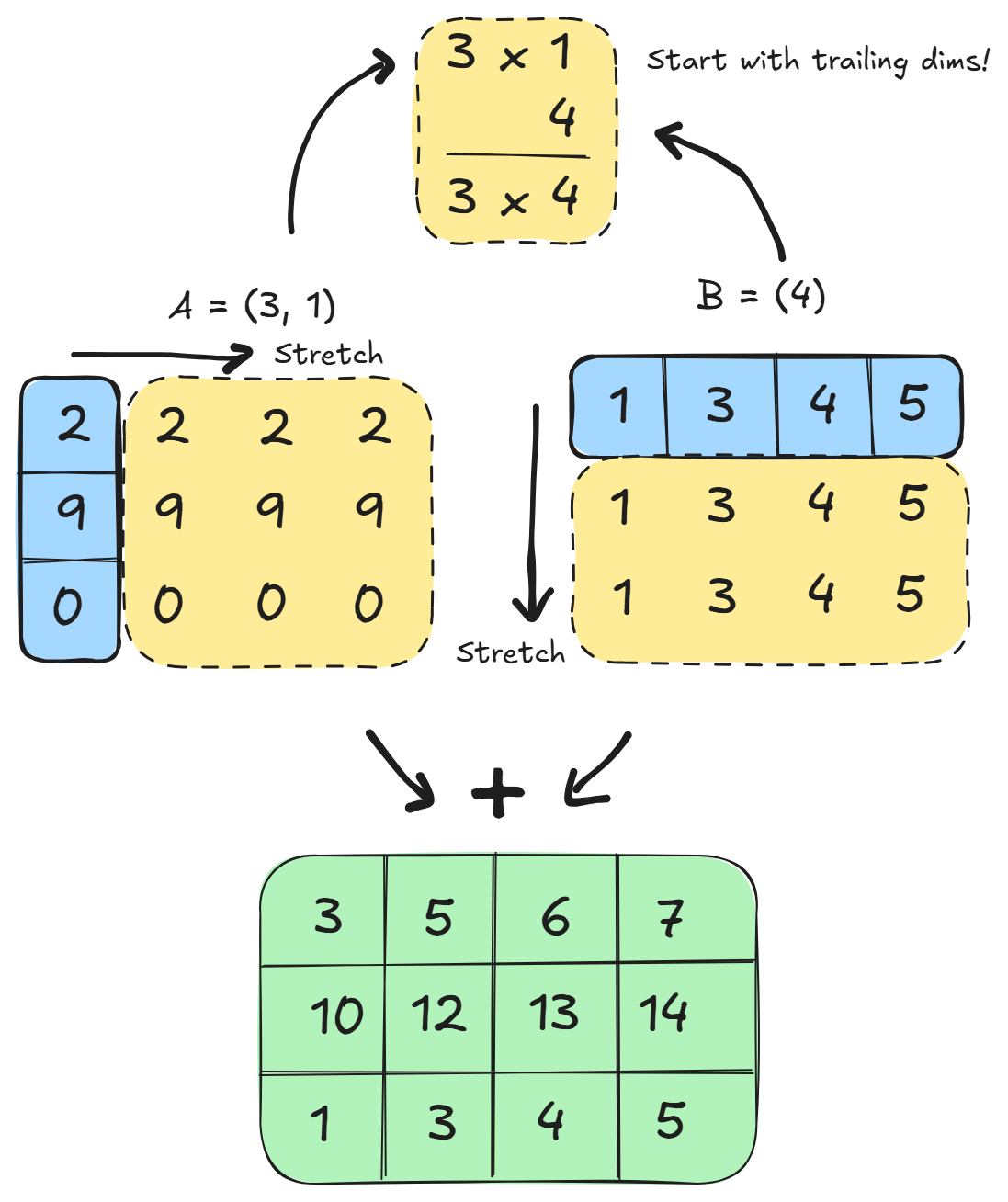

One important feature of advanced indexing is broadcasting.

In Numpy, broadcasting refers to how Numpy treats arrays with different shapes during arithmetic operations. The smaller array is "broadcast" across the larger array so they share the same shape. Broadcasting happens without needlessly copying the data, so it is efficient.

A good analogy to use is that broadcasting stretches the array to make it compatible.

Pairing dimensions from rightmost to left, the broadcasting rule for two arrays is that for each dimension to be compatible for broadcast, the two dimensions must either:

- Be equal

- One dimension is

1

The two arrays do not need to have the same number of dimensions, as missing dimensions are assumed to be 1.

For example you can broadcast:

A = 8 x 1 x 6 x 1

B = 7 x 1 x 5

Result = 8 x 7 x 6 x 5

In the above example, it is broadcastable because the first trailing dimension of A is 1, and the next trailing dimension for array B is missing and so assumed to be 1

However, if you have A = 4 x 3 and B = 4 you might think you can broadcast B to 4 x 3 but this is not true. Since we pair dimensions right to left, you cannot broadcast (4, 3) with array (4) since the first paired dimensions will have size 3 != 4.

Read more about broadcasting here.

Advanced indices are always broadcast and iterated as one. What does this mean? First indices are broadcasted to the same shape, then numpy iterates element wise over the broadcasted shape:

a = np.arange(12).reshape(3, 4)

rows = np.array([0, 0, 1])

cols = np.array([2, 3, 1])

# the result of advanced indexing will only be 3 elements!

# Elements a[0, 2], a[0, 3], a[1, 1]

a[rows, cols]

The common misconception here is that you index with the cartesian product of rows and cols. But iterating as one means that instead each rows[i] and cols[i] pair is treated as a single coordinate! Numpy is simply iterating over their broadcasted shape and taking at each position the corresponding elements of the index arrays. Think of advanced indexing as forming one virtual index array, where indices are broadcast to one shape and zipped element wise, with each zipped coordinate as one element in the final result.

For example, if one index is an array and one of the indices is a scalar, the scalar gets broadcasted. Here, it is an array of ones, and then iterating over the index elements, you get the index pairs (0, 1), (2, 1) and (4, 1).

# shape 5 x 7

y = np.array([[ 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6],

[ 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13],

[14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20],

[21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27],

[28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34]])

y[np.array([0, 2, 4]), 1]

# array([1, 15, 29])

When using index arrays across a partial number of dimensions, the shape of the resulting array will be the concatenation of the shape all indices were broadcast to with the shape of any unused dimension in the array being indexed.

For example:

# y is shape 5 x 7

# This selects the 0th, 2nd and 4th row

y[np.array([0, 2, 4])]

# array([[ 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6],

# [14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20],

# [28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34]])

With partial indexes, the unused dimensions are concatenated after the broadcasted shape, so if you have something like:

y[:, np.array([1, 3, 4])]

The unused dimension, in this case the first dimension with size 5, is actually concatenated onto the end of the broadcasted index shape (3), giving (3) + (5) = (3, 5). This can trip people up because it can lead to entirely different order of dimensions than originally intended!

Numba JIT Compilation

Often times computationally intense Python code is not easily vectorized and may have a lot of for loops with numpy operations sprinkled in. For example, this was the case when I was implementing an Enhanced Lee filter that computes each pixel based on surrounding window statistics (mean, std) with missing data edge cases. Since it was a major CPU bottleneck in preprocessing, I needed a quick way to speed up the filter. The easy solution was using a @jit decorator from numba.

The numba package provides a Just-In Time compiler for Python that works well with NumPy arrays, functions, and loops. What happens is when a JIT function is called during execution, it is compiled to machine code "just-in-time" and cached, with subsequent calls with the same type arguments yielding machine code speed.

For speeding up numerical computations in Python with numpy and loops, consider using JIT for machine code level speed.

Read more about numba here

Adding JIT is as simple as adding a function decorator:

from numba import jit

@jit(nopython=True)

def calculate(a):

trace = 0.0

for i in range(a.shape[0]):

trace += np.tanh(a[i, i])

return a + trace