Algorithms

Union Find

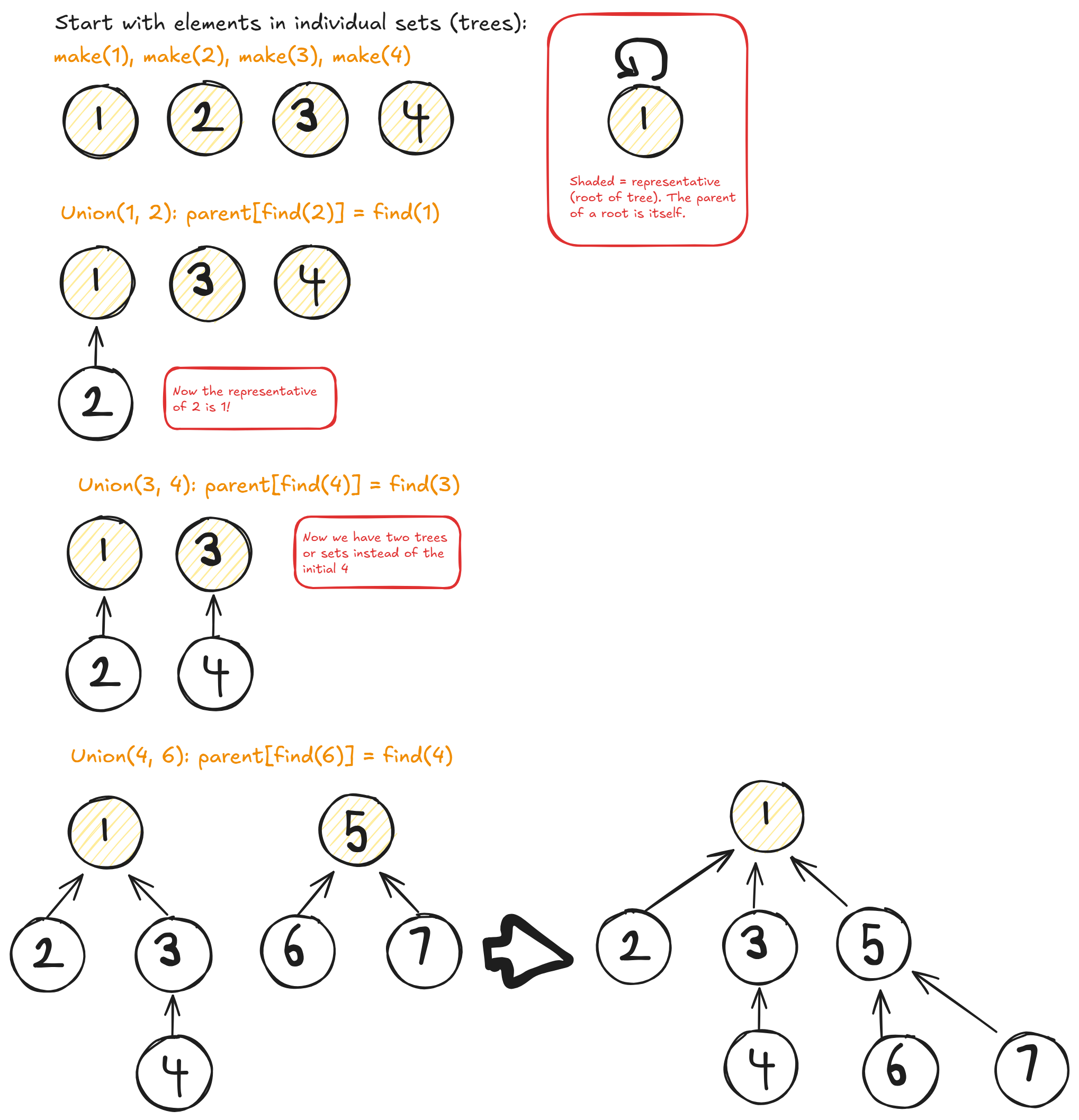

Union Find AKA Disjoint Set Union (DSU) is used to manage and combine disjoint sets. It is named after its two main operations. Starting with elements each in its own set , you can combine any two sets and determine which set an element is in:

- Union: given element

aand elementb, union the sets thataandbbelong to - Find: given element

vfind the set it is in

In pseudo code, it is usually composed:

make_set(v)- creates a new set consisting of elementvunion_sets(a, b)- merges the two specified sets thataandbare contained infind_set(v)- return the representative ("leader") of the set that containsv. The representative is an element within the set.aandbare in the same set iffind_set(a) == find_set(b).

Each set is delineated by a representative element. Elements share the same representative iff they belong to the same set.

A tree data structure is used for organizing these sets so that we can find the shared representative quickly. Each node or element in the tree has a parent. A crucial part of the implementation, is that the root node's parent is itself. Hence, a representative is found simply by checking parent[v] = v.

- Each element starts of as the vertex of its own tree

- Maintain an array

parentwithparent[x] = ymeaning the parent node ofxisy

Naive implementation:

make_set(v)- this is simple, just create tree with root asv

def make_set(v):

parent[v] = v

find_set(v)- traverse ancestors ofvuntil you reach the root (parent is itself)

def find_set(v):

if parent[v] == v:

return v

return find_set(parent[v])

union_sets(a, b)- find the representative ofaand the representative ofb. If they are identical do nothing, otherwise, make the parent of one representative the other

def union_sets(a, b):

rep_a = find_set(a)

rep_b = find_set(b)

if rep_a != rep_b:

parent[rep_b] = rep_a

The problem here is you can create degenerate trees that are just a long chain, in which find_set(a) takes and so union_sets(a, b) also takes

Optimization 1: Compress Trees

To speed up find_set(a), on the traversal from a leaf node up to the representative, set the parent of each to the representative. Thus, we flatten the tree and avoid degenerate long trees.

def find_set(v):

if parent[v] == v:

return v

parent[v] = find_set(parent[v])

return parent[v]

This results in find_set(a) time complexity .

Optimization 2: Union by size / rank

Another problem is that in the naive implementation we always attach the second tree to the first tree. This might not be optimal as attaching a large tree to a small one can lead to degenerate trees.

There are two approaches to ensure we attach a smaller tree (lower rank) to a bigger tree (higher rank):

- Use size of trees as rank

We will maintain a array size that stores the size of the tree for a root vertex v:

def make_set(v):

parent[v] = v

size[v] = 1

def union_sets(a, b):

rep_a = find_set(a)

rep_b = find_set(b)

if rep_a != rep_b:

if size[rep_a] >= size[rep_b]:

parent[rep_b] = rep_a

size[rep_a] += size[rep_b]

else:

parent[rep_a] = rep_b

size[rep_b] += size[rep_a]

- Use depth of trees as rank

Similarly maintain an array rank that stores the depth of the tree with root vertex v:

def make_set(v):

parent[v] = v

rank[v] = 0

def union_sets(a, b):

rep_a = find_set(a)

rep_b = find_set(b)

if rep_a != rep_b:

# NOTE: You do not sum depths here because the root of one tree is made the parent of the root of another

# Also if a tree with smaller depth is added to a larger depth tree this way, the depth does not change

# However if the two trees are the same depth, only increment the depth by 1!

if (rank[rep_a] >= rank[rep_b]):

parent[rep_b] = rep_a

if rank[rep_a] == rank[rep_b]:

rank[rep_a] += 1

else:

parent[rep_a] = rep_b

Time Complexity:

With both optimizations, worst case is , but on average, you have constant time queries with where for approximately all .

Resources:

Connected Components

A specific implementation for merging overlapping sets found here.

Task: Given a number of sets, union any overlapping sets until you have only disjoint or non-overlapping sets left.

For example, given the sets {7, 6}, {5, 4, 3, 2, 1, 0}, {8, 1, 0}, {2, 9}, {8, 9}, the resulting disjoint sets should be {6, 7}, {0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 8, 9}.

We will call an initial set a component and the resulting connected components groups. We maintain the following lists for book keeping:

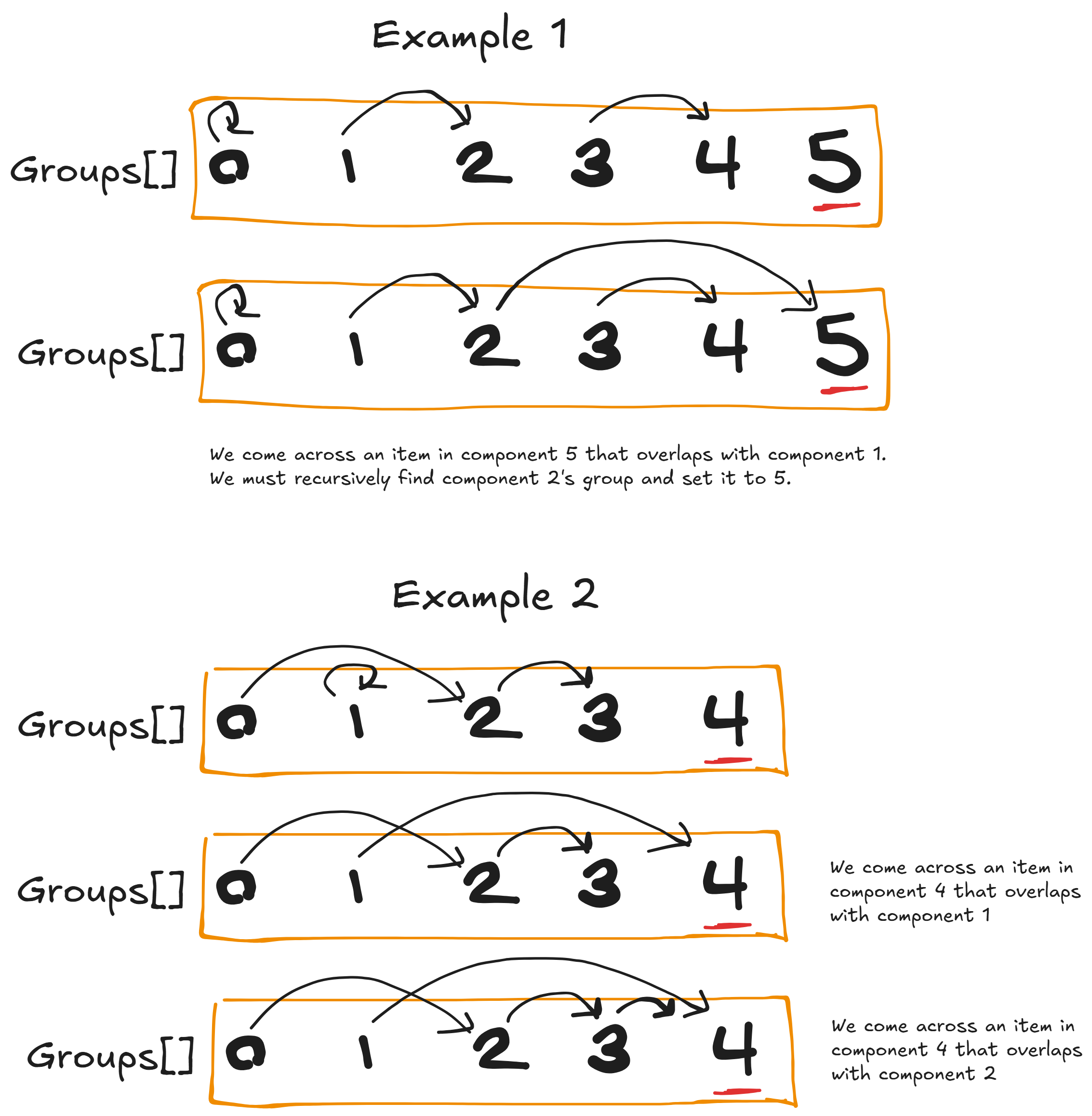

component- list of lengthn_itemsto indicate the component each item belongs to, socomponent[7] = 0in the above example.group- a DAG represented by list of lengthn_componentsto indicate the component each component shares a group with.group[1] = 2indicates that component 1 is in the same group as component 2. Ifgroup[2] = 2then it points to itself and component 2 is in its own group. Initialize with the assumption that each component is disjoint sogroup[component_i] = component_i.

To get the group of component i, if group[i] != i, then you must recursively jump through the pointers group[group[i]] until you get a component that points to itself. This is the "representative" of the actual group (see union find).

For example, group = [0, 2, 3, 3] means that component 1 shares a group with group 2 which shares a group with group 3, and the group is represented by 3.

The algorithm consists of the following steps:

- Assign components integers from

0tonand walk over them sequentially. - First walk over all components and their items, and mark them in

components. That is on componentj, assigncomponent[i] = jfor itemiin componentj. - When an items component has already been marked so

component[cur_item]is equal to some previousksuch thatk < j, this means you have identified an overlap. Mark the two components as sharing the same group. This is done by making the representative of the group ofkpoint toj. - Once all components have been walked, go from the end of the

grouplist to the beginning, propagating the value of the representative back, so instead of indirect pointers, eachgroup[i]is now equal to the representative.

By enforcing the rule that we jump to the representative component of each group, we create a DAG so that previous information and connectivity of groups is protected as we continue to add new components to pre-existing groups.

Let's walk through the tricky part of updating the groups with DAGs:

- Say you are on component 2, and halfway through it's items are unmarked in the

componentlist so you simply docomponent[i] = 2, but then you encountercomponent[i] = 1so the item already belongs to component 1. Now we want to indicate that component 1 and 2 share the same group. We do this by settinggroup[1] = 2. Say later on in component 5 we come acrosscomponent[i] = 1, if we dogroup[1] = 5then the information of component 1 and 2 sharing a group is lost. Hence we need to traverse the DAG and get togroup[group[1]] = 5. This way component 1 points to component 2 which points to component 5, preserving prior connectivity information. We illustrate this in Example 1 below.

Optimization: Breaking Up Chains in group

Supposing that the item is already marked by a previous component, we currently do the following recursive hopping:

j_component = component[item]

# suppose j_component != current i_component

# jump through DAG to representative and set its group to current component

while True:

k_group = group[j_component]

if k_group == j_component:

group[j_component] = i_component

break

else:

j_component = k_group

We can break up the possibly long chains of recursion in the group array from this naive implementation by each time reassigning the group pointers in the chain during the traversal to point to the newest (largest) representative aka the current component.

j_component = component[item]

while True:

k_group = group[j_component]

group[j_component] = i_component

if k_group == j_component:

break

j_component = k_group

Finally with everything put together our code looks like:

def connected_components(components, n_items):

"""

Parameters

----------

components : Iterable[Iterable[int]]

n_items : int

"""

n_components = len(components)

# Algorithm here

component = [-1 for _ in range(n_items)]

group = list(range(n_components))

for i_component, component_items in enumerate(components):

for item in component_items:

j_component = component[item]

if j_component < 0:

# item has not been marked

component[item] = i_component

else:

# already marked item!

if group[j_component] == i_component:

# the representative of the j_component is already the current component

# due to a previous item - so no need to do anything

continue

# jump through DAG to representative and set its group to current component

while True:

k_group = group[j_component]

group[j_component] = i_component

if k_group == j_component:

break

j_component = k_group

# Backward pass through group to propagate direct pointers

for i in reversed(range(n_components)):

if (k := group[i]) != i:

group[i] = group[k]

# Finish up by aggregating components into disjoint sets

groups = defaultdict(set)

for i_comp, i_grp in enumerate(group):

groups[i_grp].update(components[i_comp])

return list(groups.values())

Time complexity:

The algorithm requires one pass forward through the items with each component needing some recursive jumping through the DAG per item, and one pass backward through the group array.

In the naive degenerate case where each component shares an item with the first component, you will need to hop through the entire group array each time, leading to . In the best case, you do not need any recursive jumps, so it is .

With the optimization this is less problematic, though it does not always prevent long chains from forming.