Learning Git

Getting over my fear of git

How I Started

I remember before starting college, Git was a scary word to me. Mainly because I didn’t understand what it was and why it was important. All the Git commands seemed strange and obscure. I would be even more confused when people brought up Github. What’s the difference between Git and Github? Aren’t they the same thing? Why is one in the terminal and the other a website? I had lots of unanswered questions.

During a meeting with a University of Chicago grad who was working on Github developer docs, I told him how daunting Git felt to me. I asked him how he was able to learn Git, and whether there was a class out there or a specific resource to become familiar with it. He responded that I shouldn’t worry too much, and that eventually I would pick it up as a student in college. I was a little skeptical.

But he turned out to be right.

The Basics

One of the first things I learned through my intro CS class was how to use Git to clone, commit, and push my local work to a remote repository hosted on Github. This helped me understand the difference between Git and Github. Git is the essential version control system that lives on your computer, and Github is simply a service built around Git that hosts your code and helps you share your Git managed repositories. We could do without Github, but we cannot do without Git - that’s the tool you should know how to use.

To get a local git repository started, you can clone (copy) an existing remote repository:

git clone https://github.com/davdma/davdma.github.io.git

You can see the modified states of your files using git status. Then you could commit changes by running:

-

git add file.py -

git commit -m "my first commit"

To upload to the remote repository you just run:

git push

To pull in changes from the repo (when professors would add files we needed), run:

git pull

These commands were all that was needed for class.

Note: If you wanted to start a new git repository locally on your computer instead of cloning an existing one, you can just call git init in the project directory. You can always add the remote later using the git remote command.

Things to Know

Some things that helped me better wrap my head around what was going on in Git:

- Files are either tracked or untracked. Tracked means that

Gitknows about it, so you will want to make sure your most important pieces of code are being tracked. Untracked files are just everything else in the directory (if you lose untracked files,Gitcannot recover them for you). You can check the status of your files usinggit status. - Terms you will hear a lot is index and working tree:

- Staging area (Index) is the temporary area where you prepare changes to be included in the next commit. It is the bridge between the working tree and the repository’s history. Each time you run

git addit sends a snapshot of your working tree to put in the index. The purpose of the index is that it allows you to selectively stage changes for including in the next commit without doing it all at once. - The working directory (Working Tree) is the directory on your file system where the project files live. The working tree contains your tracked and untracked files and any modifications you make. The changes you make in your working directory or tree are not tracked until explicitly added to the index.

- Staging area (Index) is the temporary area where you prepare changes to be included in the next commit. It is the bridge between the working tree and the repository’s history. Each time you run

- The mental model I use is

working tree -> index -> git history. The first two is bridged withgit add, and the second two is bridged withgit commit. - Remotes are versions of your repository hosted online. In many cases, you will need to handle remotes, such as adding or removing remotes. To see what remotes you have, run

git remote -v(the flag displays the remote url next to the remote name). You can push and pull from any of these remotes!- To add remotes use

git remote add <name> <url>. You can give it any name you want as long as it’s short and easy to remember. - You can later specify the remote when pushing with

git push <remote> <branch>e.g.git push origin master.

- To add remotes use

- When you are working on a remote repository, it is important to know that there is a local representation of the remote repository that lives on your computer (if your local branch is

mainthen it is typically referenced byorigin/main). Each time yougit pullit actually runs two separate commands,git fetchandgit mergebehind the scenes.git fetch(kind of like a download) synchronizes your local remote representation with the online hosted remote representation. To get the updates in your local files thegit mergeis then done between the new local remote branch and your local branch. - When you are in a detached HEAD state, the HEAD points not to the branch tip but to a specific commit. If you make commits from a detached HEAD state those commits can be lost as they are not associated with a branch. If you intend to create new commits from a commit you checked out, make sure to create a new branch first, then make the commit.

Undoing Things

This is one of the things that stumped me for a while. How do I undo a git add? What about a particular commit? How do I revert a specific file back to a previous state rather than my entire repo?

If you want to unstage a file you have staged with git add, run:

git reset HEAD <file>

OR

git restore --staged <file>

If you want to discard changes to a tracked file, you can revert to a previous commit of the file with:

git checkout -- <file>

OR

git restore <file>

(Note: HEAD is not moved when you just revert a single file like this.)

For resetting the entire repo state (i.e. including your index and tracked files) to a previous commit use:

git reset <mode> <commit>`.

Definitely be careful with using commands that discard unwanted changes, as they may not be recovered. For instance, when using git reset <commit> you need to be aware that there are three distinct settings, --soft, --mixed (default), and --hard. The soft setting does not change your index or working tree, but simply moves the HEAD to a previous commit, so you will still have everything you staged ready to be committed. The mixed setting resets the index but not the working tree, so you still have all your changes, just not added for commit. The hard setting resets both the index and working tree, so that it permanently discards all of the changes you’ve made in your filesystem and reverts everything to that specific commit – this is the most dangerous, so use with caution.

You might wonder why there is both a git reset and git restore. git restore is an alternative and is preferable for newer versions of git. But there are some intricacies to them which I learned while trying to revert just a single file to a previous state. They sound similar, but are actually doing different things. I learned that git reset moves the HEAD while git restore does not, it only modifies your working directory. This is why git restore is a safer operation.

A useful command when it comes to probing around at file states is git diff. It shows you the difference between files at particular states. By itself without any flags it helps you look at changes between your working tree and the index staging area. If you wanted to look at changes between your index and a prior commit use git diff --staged <commit> (or --cached which is a synonym of --staged). For changes between working tree and a particular commit, use git diff --merge-base <commit>. Again, here you see why it is good to know the difference between the working tree and the index.

If you just want to see the changes introduced at a commit before you undo it, run:

git show <commit-sha>

Branching

Branching is the most powerful feature in Git, and I wish I learned about why sooner. During my software development class, I was working alongside multiple teams of students developing new features for the codebase. When you have many individuals all working on different versions of the code on your main branch, things can get hairy quick. This is why it is essential to work with different branches. Branching allows you to work on the codebase separately without affecting the main code if something breaks. In this workflow, typically the main branch (which you might be accustomed to working with) is protected, and developers cannot directly make commits to main. What you must do is branch off of main, work on that branch and make commits to it separately, and then incorporate your code later when it is ready through a pull request (PR). The PR must be reviewed by other developers before it is finally merged into the main branch.

The process of branching and merging is essential to the concept of Continuous Integration (CI) which is part of the software development process. CI prevents integration hell by frequently merging each developer’s work into the mainline branch.

To create a new branch from your current commit, run:

git branch <name>

OR

git checkout -b <name>

You can switch branches using the command:

git checkout <name>

If you just created a branch locally, you will need to set the upstream remote in order to do a git push. To set it, run:

git push -u <remote> <branch>

Note: -u is short for --set-upstream. You can also explicitly set upstream from your local branch david with git branch -u origin/david.

Merging branches takes all the changes from one branch and adds it to another using a merge commit. If you are on the david branch and you call git merge main, you merge the changes from the main branch over to your david branch. If on the other hand, you wanted to merge david onto main you would need to checkout main and git merge david from there. Often times you will want to add the newest changes from main to the side branch you are working on - to do this, you have to checkout main and call git pull to get the recent updates to main, then checkout the david side branch again to merge the updates from main in.

Merge commits are special in that it involves more than one parent commit (usually merge commits have two, but more is possible!). When merging two branches, git will look at the snapshot of the common ancestor of the two branches, and the snapshots of the two branch tips, and conduct a three way merge.

Often times you will encounter merge conflicts. This can be daunting at first, but it is actually straightforward once you learn how to resolve merge conflicts in the editor. At locations of merge conflicts there will be conflict markers <<<<<<<, =======, >>>>>>>. While most editors give the option to choose between the current or incoming change, you are free to modify the lines as you wish (e.g. if you want to choose the incoming change but make modifications or create a combination of the current and incoming change). A common misconception is that you have to choose one or the other, when you can rewrite it however you like. Once resolved and all conflict markers are removed, save the file and stage it (staging marks it as resolved), then continue with git merge --continue.

Once you’ve merged a local branch in e.g. bugFix and you no longer need it, delete the branch with git branch -d bugFix. This will keep your list of working branches organized. To delete remote branches from the server, you must run git push origin --delete bugFix.

The Powerful Git Rebase

During a talk by a software developer at Slack, he recommended that students learn to use the interactive git rebase git rebase -i. Apparently nobody knows how to use it, but it’s a superpower. This piqued my interest, so I started learning more about rebasing. So… what is rebasing?

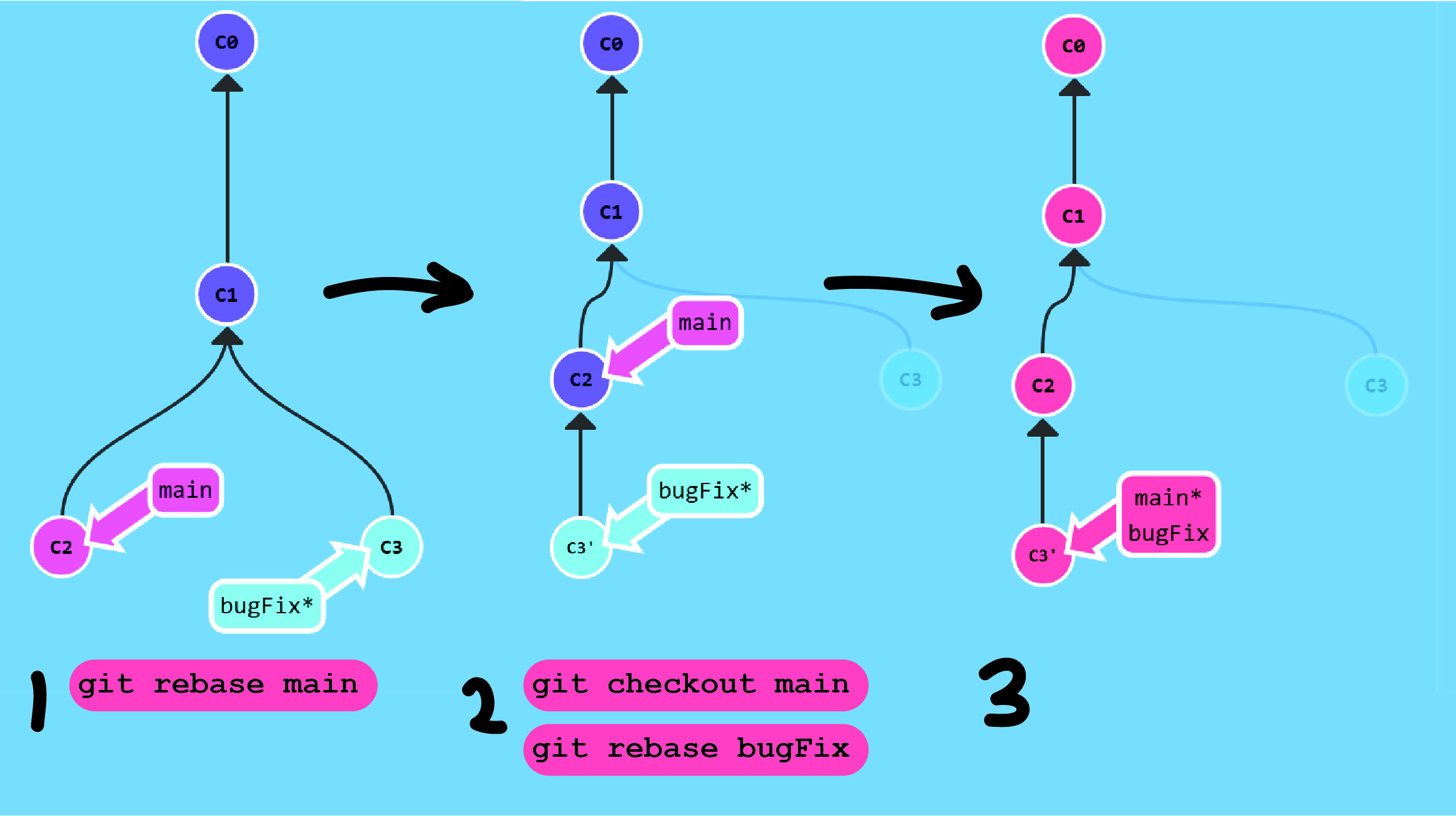

A rebase is another way to combine work between branches in addition to the merge. While a merge joins two branches together in an entangled fashion (commit with 2+ parents), a rebase creates a linearized commit history. How it works is that the rebase takes the set of commits from one branch starting from the common ancestor, and copies them over on top of the branch you are rebasing onto. In real life codebases, merging work from many developers can get gross really fast. Rebasing makes things much cleaner and easier.

Usually you would run git rebase <upstream> <branch>. But if you run git rebase <arg> it will automatically assume that the argument is the upstream branch and you want the current branch you have checked out to be rebased onto it. For example calling git rebase main from david would move the series of commits from the david branch on top of the main branch.

If you want to move work around by copying a series of commits below your current location or HEAD and you know the exact commits you want, instead of rebase you can run:

git cherry-pick <commit1> <commit2> <commit3>

But if you are not sure what commits you want or their hashes, interactive rebase comes in (and is more powerful). Interactive rebase can let you reorder commits, drop or keep commits, squash commits and even edit commits. When you run git rebase -i, you will first be dropped into your default editor (in my case vim) with the following lines:

pick 1a2b3c Commit message A

pick 4d5e6f Commit message B

pick 7g8h9i Commit message C

You can then choose what you want to do with each commit by modifying the prefix before the hash. For instance, the prefix pick means you want to keep the commit. You can also use drop to omit the commit, edit to pause and make changes, or reword to keep commit but modify its commit message. Once you’ve made the appropriate changes for the rebase instructions, save and exit, and rebase will run. Most likely you will encounter merge conflicts in the process, in which case the rebase will pause at that point. You will have to resolve these conflicts manually, add those resolutions to your index with git add, and then continue on by running git rebase --continue. If things get messy, you can always reset and try again with git rebase --abort.

If you have completed the rebase but want to go back, you can always undo the rebase by looking into the ref log with git reflog and doing a git reset.

Some important caveats: if a rebase is so much cleaner, shouldn’t we always do a git rebase then? That might not always be the case! While it is safe to rebase commits local to your computer not yet shared with other developers, it can quickly become a nightmare if you rebase commits you have already pushed to the server that other people have started to base their work on. This is because when you rebase you are essentially abandoning those original commits. (More on how to deal with this situation can be found in the Pro Git book). The best practice here is to rebase local changes before pushing and never rebasing commits already pushed.

Squashing

Another good way to make your git history cleaner is to squash your commits, i.e. combine multiple commits into one commit. You can squash commits inside an interactive rebase. You can also squash commits in a merge using git merge --squash flag. For example git merge --squash feature will take the changes from the feature branch and stage them as one giant change set, without creating a merge commit - so highly recommend using this. Doing this eliminates the long history of the feature branch, and simply adds a new squashed commit onto your main branch. If you squash merge feature with a history A (main) -> B -> C (feature) onto the main branch at A you get A -> D (main) on main where D is a commit combining both B and C.

Useful Commands

If you are jumping around commits and have uncommitted changes in your files you might lose, you will want to use git stash. Suppose you want to go back 3 commits to HEAD~3. If you don’t want to commit your current changes you will have to stash them first:

-

git stash -

git checkout HEAD~3 # now you can switch -

git checkout feature # come back to your work -

git stash pop # restores the changes you stashed

Once you call git stash those changes will disappear and be stashed away. When git stash pop is called they will be put back in your working directory.

You can inspect your reference history with git reflog. The reference logs or reflog record useful information about where the HEAD was several moves ago, as well as the movement of branch references in the local repository. It also stores recent actions. The reflog syntax @{} is important to know in addition to the ^ and ~ symbols: HEAD@{n} refers to the position of HEAD in the reflog n moves ago. Check with the reflog command what HEAD@{n} points to.

Move the HEAD to a previous reference point with all changes staged:

git reset --soft "HEAD@{2}"

Flags I Like

Options I use a lot:

- Typically for large repos with lots of files that I don’t want to store on Github, I end up with many untracked files. This can clutter the

git statusoutput. Using the flaggit status -unohowever skips displaying untracked files, making it easier to read. - Sometimes you want to just add and commit everything you modified. Save yourself some time with

git commit -aflag. You don’t even need togit add! - Interactive git adding! Often times I find myself only wanting to add a subset of the modified files for an upcoming commit, so I can have a more partitioned and organized commit history. It can be quite tedious to

git add path/to/filea dozen times. Just usegit add -ioption! The interface is a little less intuitive than the interactive rebase, but it’s easy to follow here. You can also interactively add specific parts of files if you want to split changes done to the same file in multiple commits, which can alternatively be initiated withgit add --patch. - For cleaner commit history when incorporating remote changes, fetch and rebase instead of the default fetch and merge with

git pull --rebaseoption. - For reading the commit logs, show diffs with

git log -p. Abbreviated stats (lines modified etc.) can be shown with--statand the ASCII graph with--graph. Can also limit to specific files withgit log -- path/to/file. You can also focus on specific string of interest withgit log -Se.g.git log -S some_func -p, it will look for diffs that adds or removes that string. - For reading diffs with more context, use the

-Uflag, add the number of lines you want around the diffs with an integer after the flag, for example,git diff -U8for 8 lines of context instead of the default 3. - For seeing what git files you currently have tracked you can use

git ls-files .. - Use

git branch --columnfor a neater output of branches organized into columns instead one long list if there are many branches being juggled. - To check where your branches are relative to the remote branch it is tracking from the last time you fetched (i.e. how many commits ahead and how many commits behind the remote), use

git branch -vv. Make sure you rungit fetch --allto ensure you have the most up to date remote refs.

Other things I learned of note, but I use less frequently:

- To see the authorship of lines within a file, use

git blame. The flagsgit blame -w -Cignores whitespace + detects moved lines in same commit. It’s actually recommended to dogit blame -w -C -C -Cto ignore other unnecessary stuff like who created the file (so it’s more clear who actually is responsible for code). You can use the-Lflag to narrow down the output to specific line numbers of interest, e.g.git blame -L 59,100for line numbers 59-100. You can also do something similar withgit log -L 59,100:path/to/fileto show the evolution of the line range through commits. - A safe force push

git push --force-with-leaseis always recommended over--forcewhen amending commits - Running

git maintenance startonce in any repo highly recommended! Will speed things up by allowing git to perform maintenance tasks in the background.

Aliases

For commonly used commands, it’s also a good idea to make an alias so that you can type short names. For example if you just want to type git co instead of git checkout then run:

git config --global alias.co checkout

It’s also cool to create your own commands from git command and flag combos. This would for example let you only see the last commit with git last:

git config --global alias.last 'log -1 HEAD'

Range Notation

A powerful notation within git is range notation, and can be used in most git commands. The most common syntax is the double dot A..B, and means commits reachable from B but not from A. So if you only want to see the commits in the branch featureB but not featureA from where they diverged, then you can run git log featureA..featureB. In many cases you care only about what is in your feature branch that you haven’t merged into main in which you might run git log main..feature. Preview newly fetched changes to feature with git log feature..origin/feature or preview what you are about to push to remote with git log origin/main..HEAD.

You can use it with diffs to see what changes say a pull request has introduced, e.g. git diff main..feature.

The triple dot syntax A...B focuses on commits reachable from B or A but not both. So you can look at commits of both since their divergence.

Resources

Here are some useful resources I consulted (and I still often go back to) on my journey to learning git: